- In an inflationary world, long live the strongest currencies – USD and CHF notably

- At the corporate level, this new forex order is reshuffling competitiveness cards

- Consumers too may be laughing or crying, depending on where they live and travel

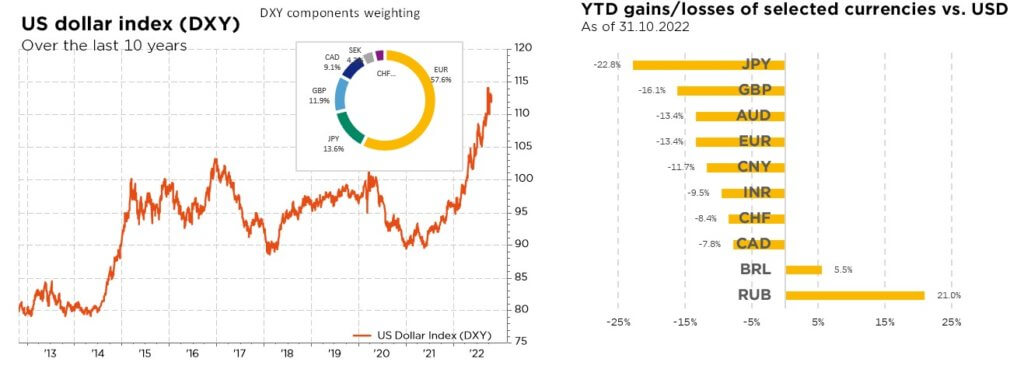

Massive stock market correction, bond crash and extraordinary greenback appreciation: 2022 will certainly be remembered as the year of many superlatives for financial markets! In contrast to the past decade, however, US authorities are not bemoaning the strength of the dollar, now at a 20-year high – nor indeed does the SNB seem troubled about the Swiss franc gaining ground vs. the euro. Rather, it is the other major economies that are expressing concern as to their currencies’ weakness. For in a world where inflation has become the biggest enemy, a firm currency is better than an (overly) weak one. In stark contrast, of course, to the deflationary environment that prevailed until recently.

Notwithstanding its huge appreciation, the dollar is not currently the most “overvalued” currency, according to purchasing power parity computations – or their more mainstream version, the “BigMac index”. Comparing the price at which the eponymous burger is sold around the globe by the leading fast-food chain, the latter (developed in 1986 by the Economist) suggests that five currencies were still more expensive than the greenback as of the end of July: our Swiss franc (+30.3%), the Norwegian (+21.6%) and Swedish (+8.5 %) kronor, the Uruguayan peso (+18.1%) and the Canadian dollar (+2.0%).

Also noteworthy is the relative strength of non-Asian emerging currencies, whose respective central banks have been more serious in tackling inflation, starting to hike key rates already back in the summer of 2021. In addition, they have benefited from the upmove in commodity prices and a “re-shoring” effect, whereby production is brought back from China to closer locations such as Mexico (to serve the United States) or Turkey (on Europe’s doorstep).

This new forex order obviously also comes with its winners and losers at the corporate level. While US policymakers are quite happy with a strong dollar – which, incidentally, also helps consolidate its status as the world’s “reserve” currency – exporting companies and multinationals that are based in the US do not share this enthusiasm. Indeed, their competitiveness vis-à-vis foreign competitors, respectively the dollar value of profits generated internationally, are diminished. Also struggling are non-US companies whose business is heavy in raw material inputs – quoted in dollar terms, therefore now relatively more expensive. Finally, all consumers based in countries whose currencies have depreciated are seeing higher imported prices further inflate their bills.

On the other side of the coin, the beneficiaries of a strong dollar are exporting companies based outside of the US (and Switzerland), which now boast lower production costs. The same goes for non-US multinationals, whose profits generated in the US have become more valuable. And of course, US (and Swiss) consumers, who are enjoying lower prices for imported goods – and can travel abroad more cheaply.

The greenback’s appreciation will not go on forever, now that almost all the Federal Reserve’s peers are also busy closing the monetary tap in a bid to tame inflation. Provided, of course, that commodity market and geopolitical tensions calm down. Still, multiple factors do suggest that the dollar will remain durably firm: higher nominal/real interest rates, the US’ relative energy and food independence, and the pending improvement of the country’s current account (thanks notably to the impact of “re-shoring” as well as greater arms and energy exports). Otherwise, it is the credibility of all central banks that could be called into question and, in turn, the global monetary/financial system. With, in such a worst-case scenario, only one big winner: gold.

Written by George Simons, Senior Portfolio Manager, CFA

Waiting for Pivot or Godot?

- To pivot or not to pivot, that is the question… for both the Fed and investors

- The emergence of a new “world order” is pushing up rates and the risk premium

- In every crisis lie the seeds of long-term investment opportunities

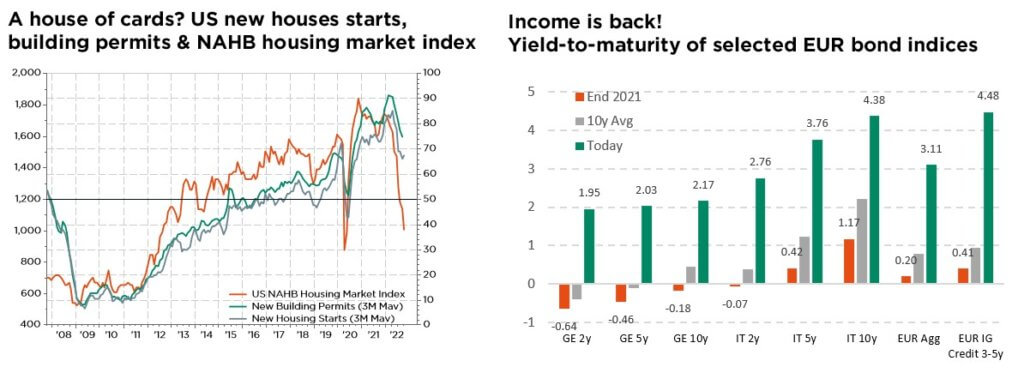

To pivot or not to pivot, that is the question. For the US central bank obviously, but not only, the debate having proven a main driver of global financial markets in recent months, rocking equity and bond investors alike between hope and despair. We see a “plateau” followed by opportunistic fine-tuning as the most likely outcome. In the meantime, global rates have continued to move higher with central banks decisively on the hawkish side, delivering further front-loaded “jumbo” rate hikes. Financial repression has thus been challenged, with long-term real rates finally moving back into positive territory and prompting a return of dreaded positive cross-asset correlations, so far making for one of the worst years on record for both equities and bonds. While further hikes are now widely anticipated, suggesting even higher real yields, the key question for equity investors is what will happen to rates when “peak hawkishness” is reached. Indeed, while a “pivot scenario” (i.e. rates to be cut at some point in 2023) would definitely be supportive for risky assets, absent a sharp recession before then, the probability of a less favourable “plateau scenario” (whereby rates stay higher for longer) has increased recently, leaving markets in a state of disarray.

As always, there are multiple moving parts in this equation. While more aggressive financial tightening across the globe has led to only modest signs of economic slowdown so far, recent high inflation has proven much stickier than expected and is unlikely to recede sharply soon, suggesting further turbulent times ahead. Meanwhile, renewed geopolitical uncertainties and lingering fears about a European energy crisis (and colder weather) have further complicated the picture. But how much of this negative scenario is already reflected in equity markets, in view of the widespread year-to-date correction? One could argue that the surge in bond yields has already taken a significant toll on (long duration) equity valuations and that gradual earnings downgrades are widely priced by now very bearish and ultra-defensively positioned investors (record high cash/low equity allocations), suggesting the worst might be soon behind for markets. That said, the central bank hiking cycle may last longer than expected and perhaps not even pivot in 2023. This would hurt economic growth hard, with the prospect of a deep recession and higher real rates weighing further on equities – while reviving the appeal of fixed income “alternative” investments. The current earnings season may bring some answers or cast another shadow over such concerns. Unfortunately, the same can be said of bond investments: higher rates and widening credit spreads are already discounting higher inflation and slower growth, but valuations have not become sufficiently cheap to fully offset the extraordinary current uncertainties.

Overall, until we reach greater clarity on the timing, duration and severity of any economic recession and the current tightening cycle, we remain on the sidelines – expecting a continued bumpy ride for global markets (equity, bond, forex and commodities) as they adjust to this new geopolitical and economic backdrop. We thus retain our near-term cautious stance (slight underweight) on both Equities and Bonds, somewhat wary of further unsustainable “bear market rallies”. Admittedly, both the valuation reset and current bearish sentiment do provide attractive long-term investment opportunities but further downside cannot be ruled out in the short run given the many inflation/growth/earnings uncertainties. With the dispersion of macro & market outcomes still remarkably large, we prefer to maintain a balanced multi-style all-terrain approach to portfolio construction and continue to advocate a well-diversified high-quality defensive equity allocation & selection. In this vein, we only fine-tuned our tactical equity positioning in October, basically reshuffling our emerging markets preferences by turning slightly more cautious on China.

Written by Fabrizio Quirighetti, CIO & Head of Multi-Asset