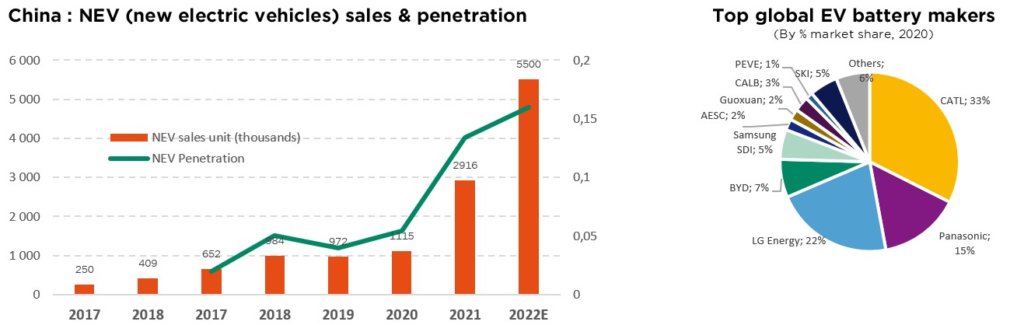

•Surging demand for electric cars has driven lithium prices to stratospheric levels

•As supply has fallen behind the curve, procurement is a key focus for auto makers

•They are also investing heavily into battery manufacturing – vying for a competitive edge

Elon Musk just made the headlines with his acquisition of Twitter. What if his next venture were to get involved in lithium mining, in a bid to secure access to this “insanely priced” white metal – and hence gain a decisive advantage in the electric vehicle (EV) market? For lithium-ion (li-ion) batteries, while still improvable, are the current best when it comes to powering greener cars (& bikes), as well as portable electronic devices such as laptops and smartphones.

If the price of lithium is up almost 80% year-to-date (and more than five-fold year-on-year), it is not because of a shortage of metal in the ground – nor indeed of capital wanting to be deployed into its mining. The problem lies rather in engineering know-how and the long ramp-up period for new productive capacity, not to mention litigation/environmental issues (Europe’s largest project in Serbia has been abandoned and lawsuits are blocking development of the US’ allegedly major lithium deposit in Nevada). Projected 2025 EV demand is such that, according to analysts, investments in lithium mining/processing would have had to accelerate already five years ago to be able to meet it. Instead, because of the lithium price collapse in 2018, many mine operators cut back on development (Albemarle, which currently supplies a third of the world’s lithium, being a notable exception). Admittedly, the auto industry itself has been caught off guard by the pace at which EV demand is now taking off, whether it be for environmental or – perhaps somewhat less laudable – social status considerations.

Accessing lithium is only the first step, though. Then comes battery production, a business into which car makers are literally pouring money. One number probably speaks more than words: USD 75 bn has been assigned to battery development and manufacturing by auto companies that together account for half the global industry.

Ford alone is embarking on the largest single spending program of its almost 120-year history, in a joint venture with Ford alone is Korean partner SK Innovation. And Volkswagen intends to build six battery plants in Europe by 2030.

The advantages of li-ion batteries are multiple. They boast by far the highest energy density of any type of batteries (albeit still ca. 100x less than gasoline), they entail comparatively modest maintenance, they have no “memory of lower capacity” issues and they do not contain cadmium, whose toxicity makes for complex disposal. Still, they do have a number of shortcomings that will need to be worked on during the next years. Their tendency to overheat was sadly evidenced by the Boeing 787 “Dreamliner” grounding back in 2013, they can get damaged at high voltages (meaning that safety mechanisms, implying both additional weight and lesser performance, need to be included), their recyclability is far from optimal, they involve sometimes unpalatable geopolitical sourcing and, last but not least, they remain expensive. On the geopolitical front, it is not so much the lithium component that is problematic, Australia being the prime producer, but other metal inputs such as cobalt (of which 70% comes from Congo) and graphite (mined largely in China). In fact, all the leading battery manufacturers are headquartered in Asia (see right-hand chart below). As for the cost aspect, batteries currently used in an EV fetch ca. USD 150 per kilowatt-hour, meaning that a pack storing 80 kilowatt-hours of electrical energy costs ca. USD 12,000 – a considerable part of the total vehicle price.

The race for lithium procurement and more efficient li-ion batteries is thus on. At stake is probably no less than leadership of the rapidly growing and hugely promising EV market. Unless the hydrogen alternative were to take an even faster lane…

Written by Sandro Occhilupo, Head of Discretionary Portfolio Management

Cautiousness warranted

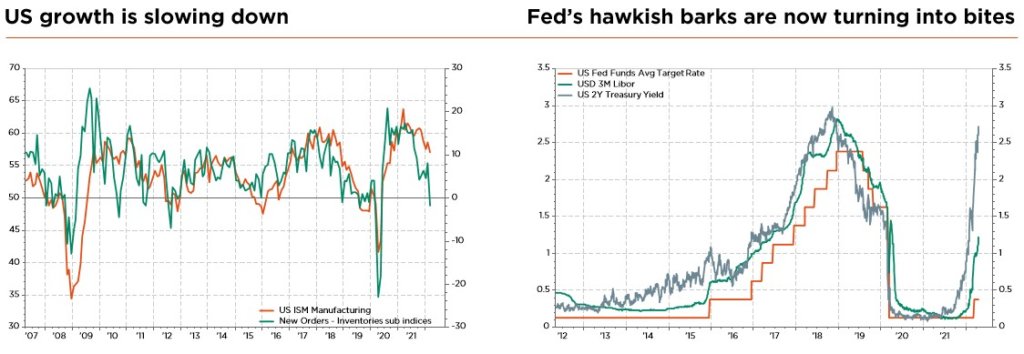

•Growth is slowing, while price pressures continue to surprise on the upside

•Keeping inflation under control has become the main priority for central banks

•Investors should fasten seatbelts in this tough context & amid the earnings season

To cut a long story short, with economies and markets now both facing several headwinds, we are turning more cautious. First concern, global growth is slowing. While we remain confident that a recession is far from imminent, risks are currently tilted to the downside, particularly in Europe given the repercussions of the war in Ukraine and the broadening sanctions. Current lockdowns in China due to revived Covid infections are also weighting on local activity, while persistent inflationary pressures in the US are restraining wage growth and consumption expenditure – hurting confidence despite the buoyant labour market.

Second, inflation will remain higher and prove more persistent than expected. Here too, the invasion of Ukraine and lockdowns in China have poured oil on the fire, adding to the upward pressure on commodity prices and further delaying the return to some form of normalcy in the global supply chain. As a result, inflation is now running at a multi-decade high in most major DM economies. Even though US price indices may have peaked, they are not expected to fall below 2% anytime soon. Inflation may indeed turn out to be stickier than in the past due to the still plentiful liquidity needing to be soaked up, to less restrictive fiscal policies – especially regarding energy transition or security – and to various cost-push pressures (supply-chain issues, re-shoring trend and tight labour market).

Finally, central bankers have adopted a more hawkish rhetoric than was expected at the onset of the year. We are likely witnessing the end of the financial repression, with monetary policy fast shifting to a more neutral stance. The Fed’s main goal is now to bring inflation back under control by slowing growth to a below-trend level. Ironically, the tight labour market and buoyant wage growth, which it had been hoping for during the past decade, have become the problems it needs to tackle.

This implies that the upcoming hiking cycle will certainly be faster than those of the past 20 years and may also last longer than expected (suggesting higher terminal rates).

This is a major paradigm shift, with meaningful implications also for markets trends and asset allocation. With inflation the main driver, while economic growth takes a backseat (akin to a dummy variable that will pop up only in the event of a severe recession), the framework that we have been using to analyse, invest and build portfolios has been turned upside down. Further, with profit margins at all-time highs and earnings growth slowing, near-term market upside may prove limited despite recent multiple compression. While there is as yet no “real” alternative to equities, given the still limited appeal of fixed income investments in the current positive growth/high inflation backdrop, it is nonetheless worth mentioning that bond valuations are improving and may soon start to offer decent returns in a world without (excessive) financial repression. That said, we continue to believe that it is too early to redeploy cash in this space.

Given the many new moving parts, we have decided to further reduce overall risk. At the portfolio level, we have thus downgraded our stance on equities from neutral to slight underweight, trimming exposure “across the board”. Again, we stress the importance of adopting a gradual and balanced multi-style approach to portfolio construction. Alternative investments have also been cut to neutral, with hedge funds facing similar challenges and thus unlikely to fare much better that long-only strategies. Finally, we increase our gold overweight as a hedge against high inflation, lasting geopolitical uncertainties and/or a looming (soft) recession risk.

Written by Fabrizio Quirighetti, CIO, Head of multi-asset and fixed income strategies