- Since the banking crisis, small- and mid-cap indices have underperformed markedly

- Near 20-year lows, their valuation arguably now already anticipates a recession

- History also shows that they outperform in early cycle – and inflationary – regimes

The time to consider increase small- and mid-cap exposure is now! Over the past few months, these stocks have underperformed their larger peers by a wide margin, to the point, we would argue, of already pricing in a recession. Together with their currently attractive valuation ratios and historically demonstrated tendency to shine early in the economic cycle, once central banks have finished hiking rates, this makes for an very interesting asymmetric profile.

Beyond rattling the nerves of investors and depositors, the recent banking crisis portends more restrictive credit conditions going forward. Not a good omen for economic growth, and certainly a clear factor in the massive underperformance of small- and mid-cap indices since March. In the US, both the S&P 400 (a proxy for mid caps) and the Russell 2000 (a proxy for small caps) have lost some 15% to the broader market – and much more relative to the handful of mega-cap stocks that are driving S&P 500 returns.

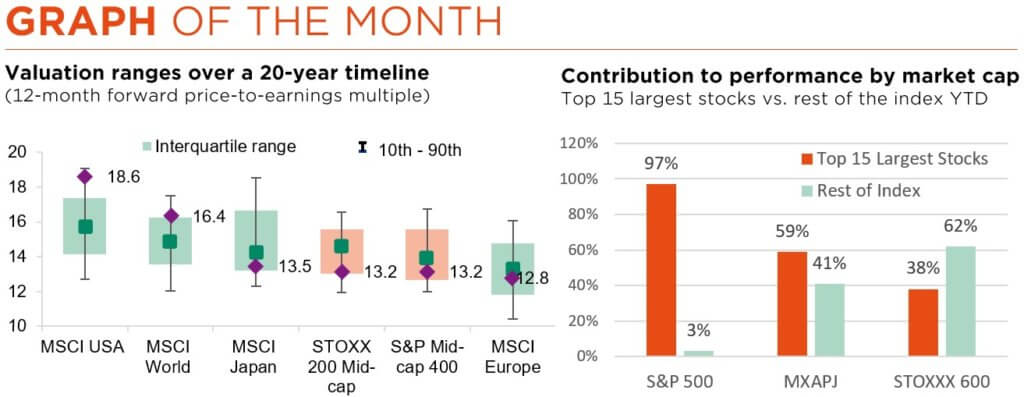

From a historical perspective, at 13.2x, the S&P 400’s forward PE ratio is near the lows of the past two decades, save for a brief period during the Great Financial Crisis. In relative terms, the valuation picture is even more attractive, with the differential vs. the S&P 500 now exceeding two standard deviations. The same – with an even lower absolute valuation – goes for the Russell 2000. In fact, plotting the latter’s 12-month forward PE (since 1985) against returns generated over the subsequent 10 years argues for what could be double-digit annualised performance going forward.

Also buttressing our case for small- and mid-cap stocks is how much further ahead than large caps they are in discounting a recession. When comparing PE levels to the ISM manufacturing index, one can indeed note that the mid-cap index has lost much more ground than the S&P 500. Whether or not a recession actually occurs, upping small- and mid-cap allocation in portfolios thus appears warranted.

Particularly since the earlier stage of an economic cycle is typically the best phase for small-cap vs. large-cap performance. Going back as far as 1979, we compute an average excess return of 8% for the Russell 2000 – with a hit rate exceeding 70% – relative to the S&P 500. By contrast, it lags on average by 2-4% during the latter part of the cycle and actual downturn.

Delving further into this early cycle small-cap outperformance, we also note how fast their earnings tend to recover from their trough. In the eight such episodes that have occurred since 1986, it took the Russell 2000 earnings only 1.42 years on average to return to their prior peak – with three quarters of that recovery achieved by the end of year one. And although complete earnings recovery was admittedly a longer process (1.87 years) in the four cases of full-fledged recession, the first-year bounce was even sharper.

What, however, of the particularities of the present cycle, made of sticky inflation and extremely rapid monetary tightening? Here again, history argues in favour of small caps: not only did they outperform markedly during the inflationary period of the 1970s, but their returns in the 12 months following the last Fed hike was also strongest at that time.

To conclude, and borrowing a quote from ice hockey legend Wayne Gretzky, one should always aim to “go where the puck is going, not where it has been”. For investors seeking to generate alpha, we thus truly believe that the time to increase small- and mid-cap exposure is now!

Written by Alexander Roose, Head of Equities

Light at the end of the tunnel? Not yet!

- Not out of the economic woods yet, while markets remain “stuck in the middle”

- The good (supportive) news: earnings, bearish sentiment and cautious positioning

- The bad (capping the upside) news: persistent valuation headwinds as growth slows

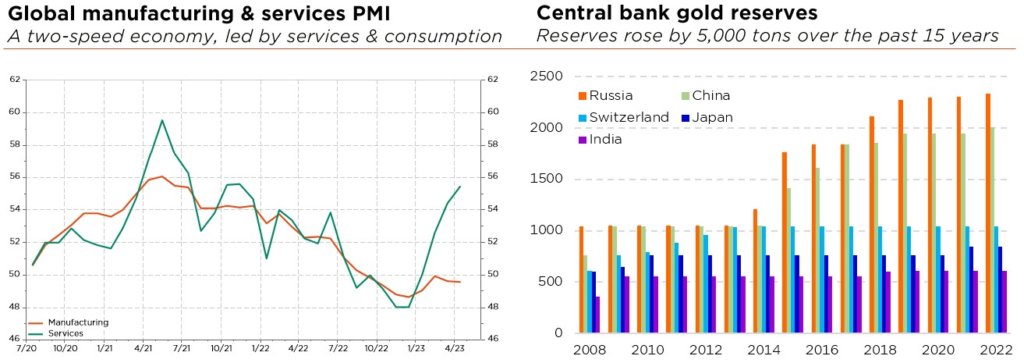

The global macro conundrum is indeed far from resolved. As credit tightening by commercial banks gradually takes over from restrictive monetary policy, with the aggressive rate hiking cycle coming to an end, inflation seems not to have said its last word and economic growth concerns have resurfaced. Recession risks remain, although the odds of a soft landing have again increased, with global economic activity proving more resilient than expected, driven by consumption and services in particular – offsetting the weakness in investment, manufacturing and housing. China’s mixed recovery also reflects this two-speed economy. Meanwhile, the peak in inflation is behind, banking stress is fading, and the labour market rebalancing continues to proceed smoothly. As for the US debt ceiling saga, it only added to investors’ wall of worry but should – at some point – be solved without damage.

First quarter earnings clearly exceeded market expectations in both the US and Europe, alleviating earlier concerns regarding sharp further estimate downgrades for the remainder of the year. We had already argued that, following a 10-15% average cut to earnings expectations over the past year, investors were already pricing in a (mild) economic recession, consistent with our own scenario and suggesting only modest additional downside. Put differently, we consider the current flat to slightly negative growth consensus for 2023 as reasonable. Still, the pain trade remains on the upside for most investors, with sentiment indicators close to negative territory and average equity allocations at historically low levels, both in absolute terms and relative to bonds. This makes for limited downside (selling) risk but also significant cash redeployment/inflow potential. We view the current set-up as clearly supportive for global equities in the medium term.

Easing financial conditions on the back of less hawkish central banks and rising odds of a soft landing, alongside diminishing stress surrounding the banking sector, have supported a lower equity risk premium. Moreover, the aforementioned improvement in earnings trends has also helped investors be more indulgent towards current equity multiples. That said, the latter are still at historically high absolute levels, while their relative appeal remains limited for most major markets in today’s positive real bond and cash yield environment. Valuation thus continues to be a concern to us, especially in the US – with both absolute and relative ratios leaving only little room to absorb additional macro shocks in what is still a highly uncertain context.

Far from “gloom & doom”, our macro scenario still foresees a marked slowdown, with lower inflation (albeit remaining above central banks’ target for the foreseeable future) and thus hawkish “wait & see” monetary policies. Instead of experiencing a major correction that could reset risky asset valuations back to more attractive levels and force central banks to adopt a more dovish stance, we rather expect a continuation of the recent trading range regime that should gradually tame valuation metrics across asset classes (equities, fixed income, real estate, private markets, …) as the focus slowly turns to a better 2024 backdrop. Admittedly, some of the market’s recent overhangs have started to dissipate. But other concerns such as recession risks or stickier-than-expected inflation remain, keeping us tactically cautious in terms of asset allocation. In particular, we require greater visibility on growth, inflation, rates and earnings before turning more constructive.

All told, we retain our cautious tactical stance (slight underweight) on both equities and bonds, but have upgraded gold to a slight overweight given the current – supportive – backdrop of debt ceiling, banking, geopolitical and inflation concerns, alongside the ongoing structural de-dollarisation of emerging central banks.

Written by Fabrizio Quirighetti, CIO, Head of multi-asset and fixed income strategies

External sources include: Refinitiv Datastream, Bloomberg, FactSet, Goldman Sachs