- February 2015-May 2023: 100 months of “Investment Insights” writing

- A period marked by major events, among which Covid obviously stands out

- But also one of remarkably strong equity market performance

In this celebratory issue, we look back to all that has occurred – in financial markets and the world more generally – during the last 100 months. And, must we say, what a ride these eight and something years have been!

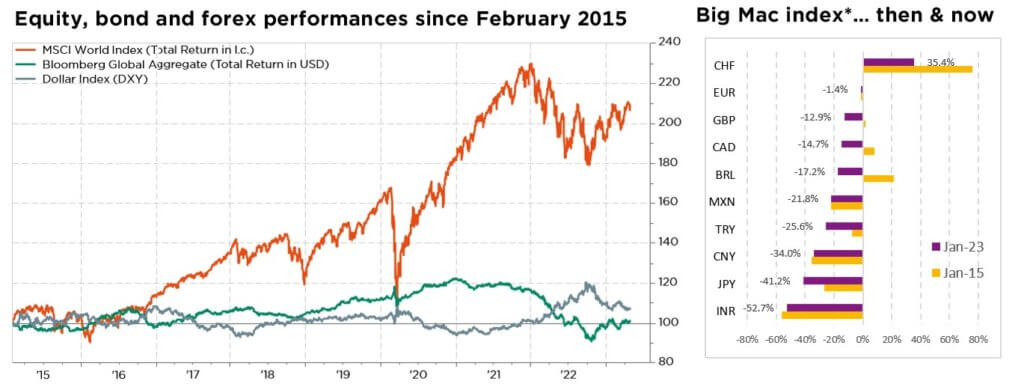

Our first “Investment Insights” was written just weeks after the Swiss National Bank (SNB) abandoned its exchange rate cap, causing the CHF to surge against EUR. This, we noted, made Switzerland the most expensive country according to the Big MacÒ index, pricing a kilogram of that McDonaldsÒ burger at par with a gram of gold. Hence our February 2015 title: “Swiss burger turned into gold!”

One hundred months later, has junk food become cheaper in Switzerland as we hoped? The 2023 update of the Big Mac index unfortunately continues to mark the CHF as the most overvalued currency – albeit by a margin that has halved since 2015. A Swiss consumer must today fork out CHF 6.70 (CHF 6.50 in January 2015) for a Big Mac burger, compared to USD 5.36 (USD 4.29) in the US and EUR 4.86 (EUR 3.68) in the euro zone.

While, in The Economist’s own words, “Burgernomics was never intended as a precise gauge of currency misalignment, merely a tool to make exchange-rate theory more digestible”, what this Big Mac price evolution mainly highlights is a lower level of inflation in Switzerland versus the rest of the western world. Indeed, exchange rates (against both the EUR and USD) are currently very similar to what they were just after the SNB’s shock decision. CHF parity against the EUR may have been an utterly unimaginable concept up until 15 January 2015, but Swiss companies have since demonstrated their ability to adapt to the new forex regime.

On the interest rate front, we have finally exited the zero-rate era that had prevailed since well before 2015. The catalyst for the 2022 policy change? Covid certainly, to the extent that massive liquidity injections during the pandemic fuelled a surge of demand amid constrained supply chains, a potent recipe for inflation – against which central banks are now fighting a difficult battle. But also the fact that governments across the globe are increasingly resorting to fiscal stimulus, recognising the need for much greater infrastructure spending, particularly when it comes to the energy transition.

Among the major events of the past 100 months, the afore-mentioned Covid pandemic certainly tops the list. Who could ever have imagined that the global economy would shut down totally for weeks on end? But other important developments during the 2015-2023 period warrant mentioning too: Brexit, a structural slowdown in Chinese GDP growth, the US-China trade war, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a hectic Trump presidency, the coming of age of ESG investment, broad-based acknowledgment of the global warming process and beginning of a mass transition to electric vehicles, the crypto and metaverse bubble, a new trillion dollar market cap club and, most recently, the demise of Credit Suisse.

From an investor perspective, the 2015-2023 period has proven incredibly rewarding. Even accounting for the pullback in 2022, especially in the high-tech (Nasdaq) arena, the MSCI World equity index boasts a near 110% return (dividend reinvested), i.e. 9.2% per annum. Most recently, Europe and Japan have regained relative ground, ditto for growth stocks (vs. value) and the banking sector (vs. energy, materials & IT). Trailing the performance table since this publication was started in February 2015 are emerging markets generally, and China in particular (up only 20-30%, i.e. 1-3% per annum).

What do the next 100 months hold in store, geopolitically, economically and financially? No doubt that the world will again have changed considerably by September 2031… mostly for the better let us hope!

Written by Sandro Occhilupo, Head of Discretionary Portfolio Management

Not too cold, not too hot, quite the contrary

- Recession odds are rising, inflation is taking a backseat and peak rates seems close

- Investors continue to climb a wall of worries… pricing in a Goldilocks scenario

- Beware of the calm before the storm, as several downside risks persist

There is increasing evidence that the recent US bank turmoil may have peaked: markets have rebounded, the VIX equity volatility gauge is back to its lowest level since the end of 2021, Fed emergency bank lending has declined, US bank deposits are expanding again after weeks of outflows, and bank bonds/equities have recovered much of the sharp losses experienced a month ago. As a result, investors are now again pricing in a rate hike at the next Fed meeting on 3 May. While a proper financial crisis has likely been averted, this “manageable” banking stress episode nonetheless likely accelerated the tightening in credit standards and loan growth slowdown that were already underway. That is especially true for small and mid-sized companies, which are far more reliant on regional bank loans than large multinationals but also more important for the US labour market (companies with less than 250 employees account for 74% of the 127.5 mn US private jobs).

Meanwhile, notwithstanding “too hot or too cold” worries that range from a greater recession odds to stickier inflation, equity markets have continued to look past the potential death valley trade-off between a growth slowdown and higher rates for longer. While a soft-landing scenario with some form of immaculate disinflation is still possible, we remain concerned by the currently unappealing valuation levels, especially in the US – in both absolute and relative terms. With the latter leaving little room to absorb additional macro shocks, downside risks abound – in what remains a highly uncertain context for growth, margins, inflation, monetary policy or geopolitics.

Far from gloom and doom, our macro scenario still foresees only a mild US recession, with one additional Fed rate hike before a pause and switch to a hawkish “wait & see” stance. Equity upside potential nonetheless remains limited in our opinion. Indeed, instead of undergoing a major correction that could reset risky asset valuations back to more attractive levels and force central banks to become more dovish, we rather expect a continuation of the recent trading range regime, that should gradually tame valuation metrics across asset classes (equities, real estate, private markets, credit, crypto… you name it) as the focus slowly turns to better 2024 earnings. In short, we still believe that most financial assets remain “stuck in the middle”. Equity valuations are capped by higher rates, while near-term earnings will be lacklustre at best due to modest top-line growth and further margin compression. Looking forward, downside risks on both equities and credit remain, in a scenario whereby the Fed could be forced to push the economy into recession in order to tame inflation.

We thus retain our cautious tactical slight underweight stance on both equities and bonds, accounting for positive real rates, higher risk premiums and major geopolitical changes compared to prior decades, as well as the advent of new reasonably valued low-risk investment alternatives. We continue to favour a balanced multi-style all-terrain equity approach, based on a well-diversified, high-quality defensive large cap allocation and selection. In fixed income, we still prefer cash instruments (to bonds) and the short end of the curve (given its currently inverted yield shape). That said, we like US duration over other sovereign bonds, as they will likely prove the best safe haven if US nominal growth peters out. In Europe, we favour IG corporates over sovereigns, with valuations still cheaper than in the US, and continue to target the upper end of the credit spectrum.

Elsewhere, we keep our tactical slight underweight on gold and other materials. Finally, we now see a lack of direction for the US dollar, so long as this scenario of low but positive global growth, without significant divergences in monetary policy trends, prevails.

Written by Fabrizio Quirighetti, CIO, Head of multi-asset and fixed income strategies

External sources include: Refinitiv Datastream, Bloomberg, FactSet, The Economist