- SVB’s failure stems from an asset-liability mismatch, not an asset quality issue

- Bank regulation, particularly in Europe, is more stringent today than in 2007-2008

- Alternatives to cash deposits are limited, leaving really two options: invest or spend!

The run on Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) happened largely online, but in essence it was no different to what generations of children have watched in Mary Poppins. When young Michael protests that he wants his tuppence back (to feed the street pigeons!), other customers question whether their own money is really “safe and sound” – resulting in the bank having to suspend business. Real-life examples unfortunately also line the pages of history books, the most recent (before the March events) being Countrywide Financial and Northern Rock in 2007.

The SVB debacle can be used as a case study of how COVID-19 impacted bank balance sheets. Massive fiscal stimulus plans, handing out cheques to households whose spending was restrained by lockdowns, led to ballooning cash balances. Businesses, too, were flush with money – particularly the high-tech startups wooed by private equity funds desperate to generate some yield. In order to achieve a return greater than what they were paying on these deposits, banks expanded their investment portfolios, notably accumulating long-dated Treasury bonds. When the Fed hiked rates aggressively, however, the problem was double. On the asset side of their balance sheet, banks experienced deposit withdrawals by customers unhappy not to see the higher rates passed through. And on the liability side, banks had to record losses on the bonds sold to honour deposit withdrawals – and shore up liquidity ratios.

There is no doubt that fintech, and the internet more generally, played a role in the recent bank turmoil. Indeed, generalised e-banking access, speedier transactions and an almost instant spreading of news across social media served to accelerate the fall of SVB. A question, though, is whether fintech can also help bank risk management departments monitor and contain liquidity shortfalls. Or whether it might foster a decentralisation of risk by helping customers spread their cash (above the insured deposit limit) across several banks.

However serious the current banking woes, we do caution against comparisons with the 2008-2009 Great Financial Crisis. Today’s issue has to do with liquidity, not solvency. Bank regulation was strengthened coming out of the crisis and, in Europe at least, these more stringent requirements have been maintained over the past decade. Banks undergo regular stress tests, are better capitalised, have greater liquidity and their funding sources are stable. At this stage, we have no indication of toxic investments, such as the CDOs of 2008, on bank balance sheets. Still, banking remains a risky activity by nature, using leverage and credit – particularly in a context of tighter monetary policy and slowing growth.

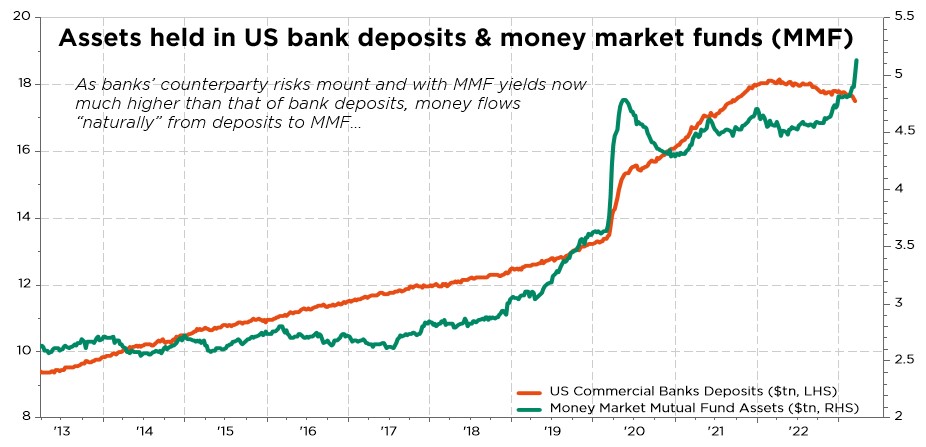

As a final word, let us reflect on the alternatives available to clients worried about cash deposits that exceed state guarantees (CHF 100,000 in Switzerland, similar across Europe). Recent developments make clear that cryptocurrencies, although born of the post-2008 lack of confidence in the banking system, are no panacea in terms of risk. Stash money under the mattress or in a home safe? Not a recipe for sound sleeping either. Rather, relatively safe instruments such as T-Bills or money market funds (perhaps not bank AT1 though…) could be purchased, insofar as financial assets belong to the bank customer in the event of bankruptcy. Investing cash with a medium- to long-term view is another possibility, or one could choose just to spend it! Particularly if a resurgence of inflation were to take a big cut out of the purchasing power of cash savings…

Written by George Simmons, Senior Portfolio Manager

The banking stress may lead to a credit crunch

- Recession odds are rising, inflation is taking a backseat and peak rates seems close

- The Fed faces a tough balancing act between inflation credibility & financial stability

- Should the central bank blink, gold would benefit and the greenback possibly suffer

One year into the Fed hiking cycle, the aggressively rapid tightening of monetary policy has finally bitten. What impact is the current banking stress liable to have on the macroeconomic backdrop? While the magnitude and extent will obviously depend on the depth of the banking sector scars, as well as the time needed for them to heal, some changes must nonetheless be factored in.

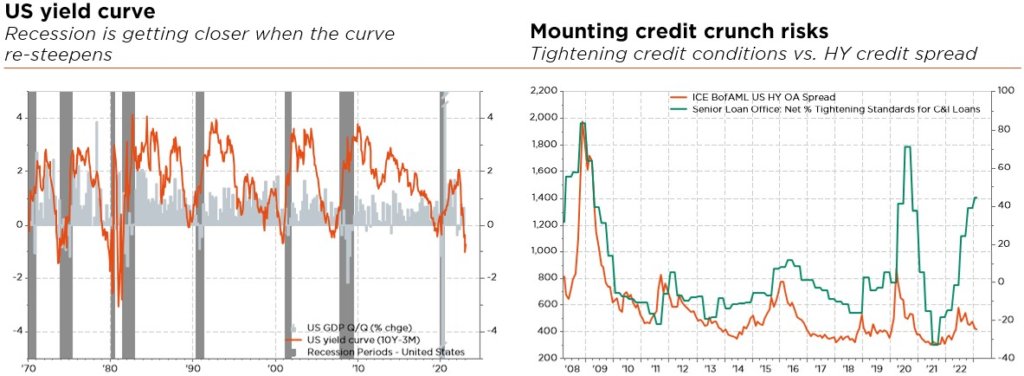

Growth prospects should be revised lower on the back of tightening financial conditions. Banks will face a higher cost of capital, some liquidity constraints and deteriorating balance sheet quality, particularly in the US commercial real estate loan space. If credit becomes harder or more expensive to obtain, especially for small- and mid-sized companies, capex and hiring prospects are likely to deteriorate. The inflation issue will certainly take a back seat, with growth slowing faster and sooner than expected and a probable pick-up in the unemployment rate. Finally, the major central banks now face a difficult trade-off between inflation credibility on the one hand, and financial stability and risks to growth on the other. Last month, they decided to proceed with a “hike-and-see” in the fact of still uncomfortably high inflation, but they also communicated a more data-dependent path going forward. In the meantime, they will continue to provide liquidity, if necessary, to solvent institutions and make sure that the transmission monetary policy to the economy is neither broken nor severely impaired. So, while additional hikes cannot be ruled out, the peak is now closer.

As a result, we retain our cautious tactical stance (slight underweight) on both equities and bonds, accounting for positive real rates, higher risk and inflation premiums, geopolitical uncertainties, as well as the relative appeal of cash on the back of its current yield and intrinsic high liquidity feature.

Within equities, we maintain a balanced multi-style all-terrain approach, through a well-diversified geographical and sectoral allocation (given the still remarkably large dispersion of possible macro outcomes), and continue to emphasise our preference for somewhat safer large-cap names. During March, we nonetheless fine-tuned our sector and factor preferences. More specifically, we adopted a more cautious stance on banks in the light of recent uncertainties, while also turning more constructive on the high-quality but still unloved technology sector.

In fixed income, we still favour cash instruments (over bonds) and the short end of the curve globally – owing to its currently inverted shape. We have, however, increased duration to the upper band of our 3-5y target range, upgrading US Treasuries to overweight. We prefer the latter to other sovereigns, as they will prove the best safe haven if nominal growth peters out and the Fed blinks. Finally, we downgrade HY to underweight, preferring high-quality fixed income amid liquidity support being removed and growth slowing. That said, we remain at ease with IG corporates, especially at the short end of the EUR curve (1-5y); valuations are still cheaper than in the US and companies usually less leveraged/more geographically diversified in terms of sales and funding.

Elsewhere, we keep our tactical slight underweight of gold and other materials. We may eventually turn more constructive on gold (and more bearish on the US dollar), should the Fed cut rates sooner and more aggressively than expected. Over the coming months, we do not foresee a major trend for the greenback – given the continued scenario of low but positive global growth, without significant monetary policy divergences. The Swiss Franc remains our preferred currency, supported by still rock-solid structural fundamentals, lower inflation and resilient growth. In the currency space too, quality and defensive features are key.

Written by Fabrizio Quirighetti, CIO, Head of multi-asset and fixed income strategies